May 15, 2011

Anatomy of an Encounter: I Could Be Wrong

As I stood in a long line at the ATM outside my bank I smelled smoke. It came and went and, after a while I started to look around for the smoker. At first, I couldn’t spot him but finally noticed the man right in front of me was holding a cigarette behind his back as he conversed with the woman in front of him. When I was young I had a severe form of asthma with no help, I’m sure, from my parents’ 1950s smoking habits. Luckily, I grew out of the disease. But to this day, I relive those years whenever as much as a simple chest cold impedes my breathing. So you can see why I don’t like inhaling secondhand smoke. Rather than passively accepting my fate, I’ve started to be a little more proactive when it comes to this part of my health. I watched him for a while, assessing his approachability, but decided not to pursue it.

Yet, I really didn’t want that smoke wafting in my face. I felt I was being held hostage in line. The next nearest bank branch was a few miles away and my lunchtime was almost up. And, yes, he was shorter than me and dressed in a business suit with no visible tattoos but you never know with smokers (okay, to be fair, you never know with anybody). I took a few steps back to catch my breath and consider my options. “Please don’t say anything,” I told myself. “Remember when you nicely asked a woman smoking just inches from a restaurant door to please move away? Don’t do it.” Suddenly I heard myself saying, “Excuse me, would you mind not smoking in line?” And with that I stepped over to the other side.

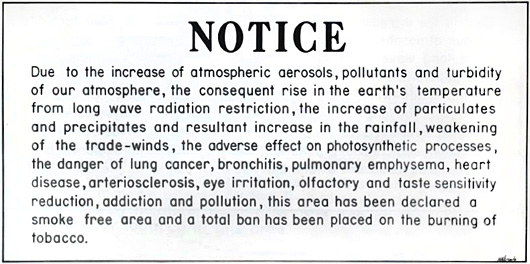

“I will throw this cigarette away,” he replied. “But there is no law that says I have to. Do you see a sign anywhere?” I noted the interesting edge to his response: initial politeness ending with a you’ve crossed that line twist. “I merely asked you if you wouldn’t smoke in line. I wasn’t demanding.” In fact, I had lowered my voice and gone out of my way to be polite so as not to embarrass him. But I was only able to get the first part of that sentence out of my mouth. He repeated his rights as he gingerly and expertly flicked his cigarette into the street.

Time began to move on two very different trajectories. Inside I was operating in slow motion. It seemed to take forever to sense his defensiveness and when I finally did I reacted with an academic’s penchant for studious and distanced observation, bogging me down even more. While outside I was trying to quickly manage both my feelings and his. His diatribe escalated. “Who the hell do you think you are? DO YOU SEE A SIGN HERE?!” I looked to others in line for support and solace (a knowing nod of exasperation would have been enough). But there was no eye contact. Nothing. They had already decided not to fight this fight.

I tried one more attempt at reconciliation but it was a lost cause. It was only then I successfully shut myself up. I was seething. And so was he. As I walked away from the ATM, money in hand, time and fresh air allowed me to clear my head.

Control was the primary objective for both of us. Most smokers know smoking is a nasty and unhealthy habit. And there is a long line of loved ones and doctors telling them to stop. But we know how difficult it is to quit. I wanted him to stop smoking; he wanted me to stop reminding him how difficult it was for him to do so. But instead of that realization he got pissed at me for impinging on his “rights.” I was tired of feeling trapped in open air by smokers passing me by on the street; he was tired of society’s allowable, but slowly shrinking space in which to pursue his habit. In our own way we both felt trapped. And we were both pretty angry about it.

Was I wrong to engage him? Kathryn Schulz, author of Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error, calls this error blindness. In her recent TED talk she said: “Most of the time, we don’t have any kind of internal cue to let us know that we’re wrong about something, until it’s too late.” It was too late for me when I realized I might be wrong —not wrong to want a smoke-free environment. I was wrong to think I could tell this man how I felt without consequences, or, from his point of view, how to run his life. I anticipated the possibility, but my sense of righteousness propelled me forward anyway. “…Trusting too much in the feeling of being on the correct side of anything can be very dangerous,” Schulz continues.

This is a male, “power meets power” thing. And none of it is very pretty. At the very root, I felt humiliated. This is what men feel when they’ve lost control. No one talks about it much. It’s an intense emotion with no outlet other than venting (unless you learn to talk or write a story about it). Angry men are often humiliated men. And it takes a huge amount of effort to come down from that precipice. When I made that very conscious decision to shut up (after my second attempt) it took a gargantuan amount of energy to do so—to take a step back.

Schulz:

Think for a moment about what it means to feel right. It means that you think that your beliefs just perfectly reflect reality. And when you feel that way, you’ve got a problem to solve, which is, how are you going to explain all of those people who disagree with you? It turns out, most of us explain those people the same way, by resorting to a series of unfortunate assumptions. The first thing we usually do when someone disagrees with us is we just assume they’re ignorant. They don’t have access to the same information that we do, and when we generously share that information with them, they’re going to see the light and come on over to our team. When that doesn’t work, when it turns out those people have all the same facts that we do and they still disagree with us, then we move on to a second assumption, which is that they’re idiots.

It would be so easy for me to say that guy was an idiot and be done with it. “Piss on you!” I could say to myself and walk on. (Or, knowing I have little self-control I might say it out loud and run.) But, that’s just it. I have an inner voice. Without it I’d only have my anger. Schulz says “We love things like plot twists and red herrings and surprise endings. When it comes to our stories, we love being wrong.” So, why not in real life?

Maybe I was wrong to engage this guy. If I wait just a few more years perhaps I won’t have to ever do it again. New York City’s Mayor Michael Bloomberg has signed into law a smoking ban in parks, beaches, public plazas, and boardwalks. And, if I want an even better ending to this story I’ll imagine that maybe, just maybe, that guy with the cigarette wrote a story about our encounter too. Perhaps he also entertained the notion that he was wrong. Oh, hell, who am I kidding.

View Most Recent Story![]() :::

:::![]() Notify me when there's a new missive!

Notify me when there's a new missive!

ShareThis

ShareThis