December 14, 2008

The Diving Bell and the Brain Tumor

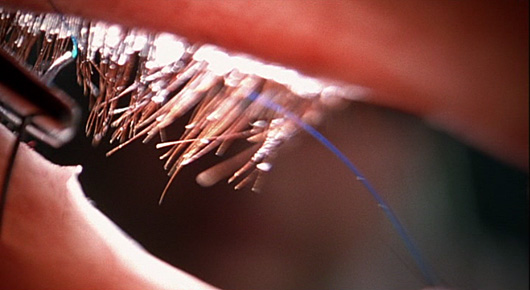

From his vantage point: sewing Jean-Dominique Bauby’s eye shut after his stroke. Still from the film The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.

Today is my mother’s birthday: more accurately, the 87th anniversary of her birth. She died in 1971 just days before her fiftieth birthday. Eleven years before she was diagnosed with a benign brain tumor: acoustic neuroma, Clinically speaking, this tumor is “a non-cancerous growth that arises from the 8th or vestibulo-cochlear nerve.” But the effects of her illness and treatment were as toxic as any chemotherapy would have been. At 11 I was too young to be included in the discussions of her disease, prognosis, and treatment. Invasive and targeted, today my memories of her illness are still as imbedded in my brain as her tumor was in hers.

Yesterday, while the rest of the family was out on holiday errands I decided to force myself to watch the Netflix movie that had been sitting next to the TV for months. Next in our queue was The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. While I couldn’t remember the film’s exact synopsis I knew it had something to do with a man locked in his body, unable to respond to the world around him. This certainly wasn’t on my list of comedic films I’d gravitated to recently, hence its longevity on our TV shelf. And as the plot unfolded I was totally unprepared for the striking similarities to my mother’s illness the film would convey. I was shocked at how raw my feelings and emotions were 48 years after the fact. And I was glad I was alone.

In the film, an adaptation of Jean-Dominique Bauby’s autobiography, the author describes the after-effects of a massive stroke that paralyzed most of his body. While there was nothing wrong with his ability to think and feel he was totally unable to move or speak. He was, as his doctors described, locked into his own body.

After my mother’s operation she too had been transformed. She didn’t have a stroke but the results of her operation left the right half of her body fixed and immobile. When Bauby’s neurologist first exams him and sees his right eye is not blinking I suddenly remembered my mother’s eye. His eyelid, my mother’s eyelid had to be sewn shut in order to preserve it. And the graphic nature of director Julien Schnabel’s depiction, shot as seen from Bauby’s eye as it’s being sewn shut was almost too much to bear. But I forced myself to look, ironically through cupped hands over my eyes. Usually reserved for horror movies, it’s a control mechanism we all use. Too much and we can quickly black out the horrific parts. I was prepared now but it hadn’t always been that way.

Until now I had always experienced my mother’s illness from an 11 year old’s perspective. I, too, had been locked in position all these years. Suddenly, I was experiencing it from my mother’s point of view. When we first see Bauby’s face, we see the sutures cementing his eyelids together. And his lips, the right sides of which are limp and distorted, brought back similar memories. The scene was only a few seconds long but it was as if this was a vision I’d had for decades. In fact it was.

When my father came into my bedroom that evening, he sat me down and told me mom would have to have an operation. She had lost part of her hearing in her right ear and often would feel a sense of vertigo. The doctors had diagnosed the tumor and it had to be removed. I remember feeling scared but in a child’s way. My initial fears were not of death. I’d never experienced death before. They were more about change. What did this mean to me?

On the day of her operation I went to school. I felt special as I played during recess. My mother was going to have an operation today! Turning the day into a special event was my way of pushing away the fear. A couple of days later we went to the hospital for our first visit. That’s when my special event was replace by my new reality.

They brought my sister and me into a room. It was painted that dingy hospital green. We were sitting on a bench when they wheeled my mother in. Her hair had been cut and she had little clamps on her right eye to keep the lid shut. We engaged in that inane small talk that’s so typical of hospital room visits. My father was there and so was the 800 pound gorilla. We ignored the primate while my mother started to ask us questions. “Are you doing what grandma says?” she uttered. Her mouth transfixed me. Only half of it was moving.

At first Bauby doesn’t remember having his stroke. But his memories slowly return. He had just picked up his son in his new sports car to take him to the theater. They are driving along a country road engaging in father-son small talk. “Got any hair on your dick?” Bauby asks his son. “Not yet!” his son replies. Such an open and loving exchange, it reminded me of last week’s dinner conversation when my 10-year-old daughter suddenly announced that “Mom and I had a talk about periods today.” “Well, what do you think?” I asked. “Yech,” she replied. As the stroke begins we witness Bauby’s transformation. This would be the last normal conversation he would have with anyone.

As his son realizes the gravity of the situation and runs to the nearest house, the look on Bauby’s face is excruciating. His foot is glued to accelerator, spinning his tires. His contorted expression is part stroke and part realization that something awful is happening to him. He’s losing control of his body. Later we witness his shock at who he has become: “God, who is that? Me?” What did my mother think the first time she saw her face? I don’t remember what I thought and we aren’t clued in to what his son thought in later visits with his transformed father. Schnabel story is meant to be seen through Bauby’s “eyes.”

And through his eyes I connected with my mother’s life. While she could speak and walk with the help of a cane she always complained that she was in a “fog.” As a boy I was disconnected with those feelings. But on the eve of her birthday I was given the opportunity to remember her, not through my life but perhaps through hers.

Related Post: On Death and Waiting: making the hard decisions in the Terry Schivo case

View Most Recent Story![]() :::

:::![]() Notify me when there's a new missive!

Notify me when there's a new missive!

Comments

Jeff: this is so moving and brought me back to my own mother’s illness and her shortened life. I think when we’re young and experience loss something closes around us. Sometimes, later in life, we’re able to open and see. As a writer I admire how you were able to weave the narratives together; as a friend, I’m extremely moved. Thanks for writing/sharing this.

Posted by: Howard on December 14, 2008 4:02 PM

Comments are now closed for this post. But there are a few other entries which might provoke an opinion or two.

ShareThis

ShareThis