Clearing the Path for Sisyphus

How Social Media is Changing Our Jobs and Our Working Relationships

Social media is changing the inner workings of our museums. Like many other organizations, our hierarchical structure has historically disseminated information from our experts to our visitors. The envisioned twenty-first-century model, however, is more level. Instead of a one-way presentation, our online visitors are often interested in conversing with our curators and content providers. And many of us are joining our traditional experts in representing our institutions in these conversations. In response, we in new media have been looking for ways to engage our public by designing and using applications that encourage dialogue. However, to succeed, we will need to approach our jobs and our relationships with our coworkers in different ways.

While the early hope of many technorati was that the Web would dramatically change the inner workings of our cultural institutions, new media’s role began as a support for more conventional projects—exhibitions, outreach, and our collections—with web-based counterparts. But as new Web 2.0 tools developed and we saw the possibilities for a greater engagement, we often felt like Sisyphus. We heard concerns that these new initiatives would take too much time or take away from our institution’s core tasks. And just when we thought we had made inroads, the boulder would come crashing down: one step forward, two steps back. Our work was to function within our traditional organizational structure. Yet, these first steps were just a prelude to real change.

While the early hope of many technorati was that the Web would dramatically change the inner workings of our cultural institutions, new media’s role began as a support for more conventional projects—exhibitions, outreach, and our collections—with web-based counterparts. But as new Web 2.0 tools developed and we saw the possibilities for a greater engagement, we often felt like Sisyphus. We heard concerns that these new initiatives would take too much time or take away from our institution’s core tasks. And just when we thought we had made inroads, the boulder would come crashing down: one step forward, two steps back. Our work was to function within our traditional organizational structure. Yet, these first steps were just a prelude to real change.

Social media is now challenging the traditional flow of information throughout our institutions and out into the world. Researchers, educators, new media specialists, and exhibition designers are asking to join marketing and public affairs departments to convey our museums’ mission to our visitors. Blogs, Twitter, and Facebook, just to name a few social applications, allow for and encourage multiple institutional voices.

But how is this transformation really taking place? Are there methodologies that encourage this shift? And how do can we negotiate with our peers a more significant role in content creation and dialogue? How can we challenge existing paradigms yet maintain the support of our coworkers?

Those of us at Smithsonian American Art Museum are working on two levels: as part of critical Smithsonian-wide initiatives, like Flickr Commons, and directly within our museum. In March 2009, I discussed social media’s new roles for museum professionals in an article titled Confessions of a Long Tailed Visionary. Rather than just disseminating important cultural information to our visitors, we added new roles to our jobs as we began to engage our public in conversations about our museums and our artworks. We were exploring new connections, advocating for change, collaborating to create new forms of dialogue, and organizing these new communities in ways that would benefit both our visitors and the museum.

In the months since penning that article, I’ve been looking more closely at how we can more effectively embrace this change. And in doing so, I’ve started to explore how social media is changing our jobs and our working relationships with our coworkers. Adding to the five new tasks I outlined in 20091 are system analyst, negotiator, and opportunist. How can we work together to promote this change and increase our public network? How do we negotiate with our colleagues as we parse out these new working relationships? We need to be agile, taking opportunities whenever they present themselves to develop, evaluate, debate, evangelize, move forward, and even slow down when the process warrants. During this often volatile period of change, what strategies work best for clearing that social media path for Sisyphus?

A Case in Point

One of our most successful pre-Web 2.0-outreach programs was our “Ask Joan of Art” research service. For the past seventeen years, people were able to submit questions about American art to a research team at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and receive a detailed answer to their queries via private email. Over the years, “Joan” amassed an extensive repository of useful information. But none of it was available to the public. And when the New Media Initiatives department suggested we put this information online, coworkers resisted.

Some thought we had more critical short-term priorities. We had just completed a major revamping of our website’s information architecture. And we had to put on hold many projects while we completed this enormous task. Our stakeholders were eager to get back to these. While New Media Initiatives saw many Web 2.0 opportunities, we had to balance this with our more traditional service-oriented duties. So we had to be strategic when adding these to our everyday workload.

In addition, “Joan” used several proprietary subscription-based publications, like Oxford Art Online, Art Full Text, and Art Index, to answer these questions. These are full-text citation indexes, and the Smithsonian’s General Consul’s office was concerned that making this comprehensive information public might present a copyright infringement. We could have made a case for educational fair use. But our lawyers’ concerns presented a roadblock we needed to deal with.

Simultaneous to this discussion, Kathleen Adrian, the person who ran “Joan of Art,” began tweeting questions about American art, but only the questions. Following her, I saw an opportunity and asked if she’d be willing to answer those questions on our website. By posting the question on Twitter and a link to the answer on a new page on our site, we would bring these answers to the public and bring followers back to us, creating a synergy between Twitter and our museum website. Adrian was willing but needed to structure the answers not to jeopardize the copyrighted material she mentioned in her private responses. So she started to post answers into an informative yet less academic form for our public site. In addition, posting the question and answer on our site in a comment format (using a third-party commenting application called Disqus) allowed the public to interact with Joan should they have additional information to contribute or any follow-up questions.

Working together, we found a way to navigate around these initial barriers to bring this content to the surface. But it required looking at how we could structure the content and our systems to make it happen. Adrian had opened the door when she began tweeting on her own. New Media worked with her to build an information flow that benefited the reader and the museum without jeopardizing our other work.

The project ran from July 2009 until September 2011, and in that time, we posted eighty-two Ask Joan of Art answers online, and over 3600 people viewed them and asked their own art questions. This is not a huge number in the scope of museum Web statistics as a whole, but gratifying when you consider this information wasn’t available to the public before this project.

After a few months, we built up quite a repository, so much so I started to become concerned that some of this would become buried once again at the bottom of the question and answer page. So I went to Adrian with an idea: let’s repurpose these questions and answers as posts on Eye Level, our museum’s blog.2 The material was already written and would require only minor editing for style. Since we had already navigated the tricky copyright issue, it would be easy to provide another outlet for information about the museum’s artworks and bring this content back up to the surface to an expanded audience. And, by taking this path, we were able to do this quickly and with a minimal amount of decision-making “by committee” or higher-ups. Despite the end to Ask Joan of Art, our Research department continues to contribute information from this project to Eye Level once a month.

As a coworker so aptly stated, the methodology used to make these additions to “Ask Joan of Art” could be categorized as a “conspiracy to commit progress.” The New Media Initiatives department recognized the need to bring this content to the surface, but we also noted initial objections. Noticing the initiative of our coworkers to experiment with social media, we saw an opportunity to move forward. We encouraged a discussion on how we could use this to meet one of our most important Web 2.0 goals: bringing buried content back to the surface. Working together, we then devised a strategy that resolved copyright concerns, was easy to implement (no added work), and value-added (created a synergy between our social media efforts and our traditional museum website).

Adjusting Our Social Media Outreach: Case History II

At present, the American Art Museum has three Twitter and three Facebook feeds (each managed by a different department) 3 and one Flickr account (used by numerous departments but managed by New Media Initiatives). New Media Initiatives also runs our blog. In 2009 all of us involved in the museum’s social media efforts decided to form a working group to discuss and coordinate our various Web 2.0 activities and plan for coverage of upcoming exhibitions and events.

The museum has been using Twitter since September 2008.4 We tweet about upcoming public programs and point to our web-based content, including our blog, Facebook posts, and our Flickr stream. As social media is evolving and with different museum models now presenting interesting examples of how other institutions tweet, it seems like a good time to take stock of where we are and whether we want to move this outreach to another level.

There are several things we can explore. Could we increase the frequency of our tweets efficiently? Did we want to add additional voices? To fine-tune our outreach on many different social media platforms, how can we find out more about our followers? In addition to the content we were already tweeting, is there anything new we could add to the mix? Specifically, is there any “low hanging fruit” we could pick to bring content back up to the surface to additional audiences?

We average about 1.8 tweets/day. By comparison, the Museum of Modern Art tweets 3.4 tweets/day, and our sister Smithsonian institution, the National Museum of American History, tweets 4.8 tweets per day. Should we consider increasing our activity using software like Hootsuite5 to allow us to “bank” tweets for publication later? Most of our tweets occurred during weekday business hours. The Modern’s was skewed a bit more into the evening hours while the American History Museum tweeted much more frequently during the weekends. In addition, is there value in retweeting our tweets multiple times? With the quick flow of Twitter, people might not see our tweets the first time around, and a second one, perhaps restated to look fresh, might be a good idea. Being able to create and publish our missives at a later time might be helpful.

In a recent Museums Etc webinar, Twitter in Action,6 we learned that some museums used only one tweeter while others used multiple ones. Would it be advantageous to us and beneficial to our public if we had numerous tweeters, each talking about different aspects of the museum? A steadier stream of tweets might gain readership. But we didn’t want to add noise to everyone’s feed. So if we were going to increase our stream, we’d need to find good content. But, once again, we faced the Web 2.0 dilemma: too many good ideas and not enough time. Who was going to create this content? Did we have any quality “low hanging fruit” we could repurpose?

Could “1001 Days & Nights of American Art” be our Twitter “low hanging fruit?”

Could “1001 Days & Nights of American Art” be our Twitter “low hanging fruit?”

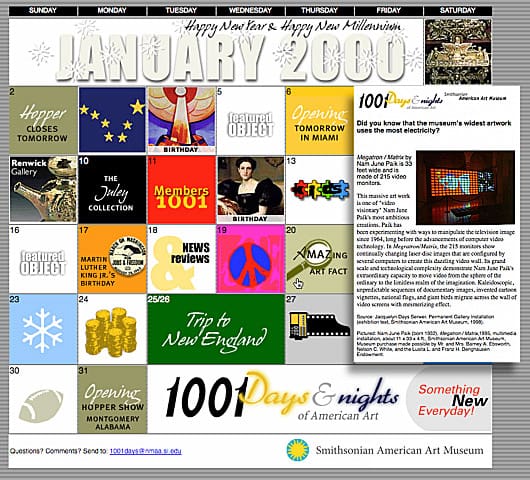

In 2000 we created “1001 Days and Nights of American Art,” our first major online venture during the museum’s renovation. We had planned on being closed for about those 1001 days (truth be known, it turned out to be over twice that amount). And we wanted to create a calendar of interesting facts about our collection during the period we were closed: one each day. It was another one of our pre-social media endeavors. While our building was closed, we were open online, and we wanted to remain connected to our visitors.

Designed and edited by hand each month, it was a considerable effort supported by numerous departments in the museum and one that was begging to come back to the surface ten years after we first launched it. The question now was how to create a process that would allow us to do so with minimal work. Using our experience with “Ask Joan of Art,” perhaps a similar model could be used with 1001: tweet a teaser with a link to a new page on our website.

Our Public Affairs department produces our tweets. How these ideas (or any new ideas) will fit into their present model and workflow and how receptive they will be to these suggestions will be part of our initial discussions and negotiations. Like “Joan of Art,” the content has already been vetted: a big time saver. Should we move forward, we would do a system analysis of the most efficient way to repurpose “1001” with an emphasis on minimizing the extra workload for everyone.

So what have we learned from these experiences? The social media aspects of Ask Joan of Art began when a museum worker started tweeting on her own, under the radar, and without committee discussion. Expanding its functionality by building a connection between Twitter and our museum’s website first required us to see the bigger picture: matching the promise of social media with the specifics of our museum’s programs and outreach. Under these circumstances, it seemed natural for a few of us to conspire to commit progress. Extending our museum tweets, however, will require discussion, negotiation, and collaboration.

Interestingly, both of these methodologies are hardly revolutionary in organizations. However, as we are becoming seasoned students of the shifts taking place in the 21st-century museum, we can act as advocates and guides for the changes taking place in museum practice. By keeping in mind our core mission and connecting it to our social media practice, we can make our case for a more robust online engagement with our audiences. It is essential that our stakeholders know that we won’t throw out what has worked just for the sake of social media and “the next best thing.” Coming across as reasonable with an eye to that next online development will encourage open discussions and negotiations, moving us forward.

There is no silver bullet to the success of these new Web 2.0 projects. Time, money, and personnel are still the anchors to success. And strategic fact gathering, good proposals, and excellent negotiation abilities are still critical in a social media worker’s skill set. While new tools for connecting museum assets to our larger communities are announced almost daily, developing and integrating them into our workflow requires good traditional people-to-people management skills. But the desire to present our content and extend our connections with our online public in new ways has increased the need and urgency to fine-tune our ability to work well with our coworkers. The boundaries between museum departments and our job descriptions are becoming porous and ever-changing. Sisyphus still may be rolling that boulder up a hill, but it is getting smaller and easier to push forward.

Endnotes

1. The five new roles outlined in Confessions of a Long Tail Visionary were Explorer, Advocate, Collaborator, Community Organizer, and Realist.

2. Eye Level, http://eyelevel.si.edu

3. Update: As of 2011 it was decided that our main social media outreach would be handled by one department: our renamed Media and Technology department (formerly Information and Technology).

4. Smithsonian American Art Museum Twitter feed, http://twitter.com/americanart

5. Hootsuite, http://hootsuite.com/

6. Twitter in Action, Museums Etc, http://www.museumsetc.com/?p=1416

7. Cite as: Gates, J., Clearing the Path for Sisyphus: How Social Media is Changing Our Jobs and Our Working Relationships. In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). Museums and the Web 2010: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2010. Consulted March 31, 2010. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2010/papers/gates/gates.html

© 2010-2021 Jeff Gates. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License.