Confessions of a Long Tail Visionary

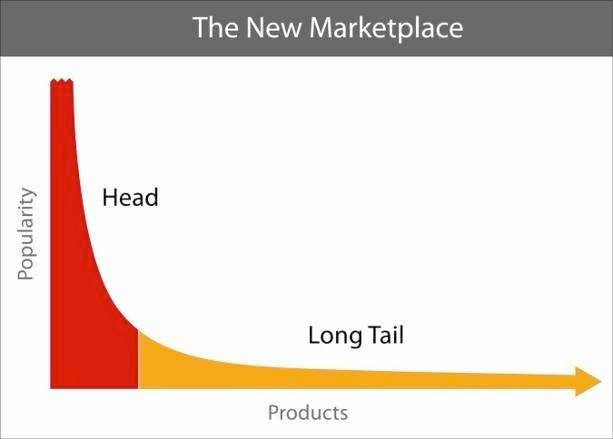

Chris Anderson’s The Long Tail: Products that are in low demand or have low sales volume can collectively make up a market share that rivals or exceeds the relatively few current bestsellers and blockbusters.

Chris Anderson, the editor of Wired magazine, popularized the term The Long Tail to describe a strategy for businesses that sell large numbers of items, each at a relatively low volume.1 Despite fewer sales per item, according to Anderson, such companies can make big profits if they reach many, many niche buyers.

In the last few years, the Smithsonian American Art Museum has been looking at our museum’s online information in the same way. Our web statistics showed that the number of visitors to our top ten sections paled compared with the total number of visitors for all other pages, even though only a few people viewed each page. The challenge: how could we make it easier for our online visitors to find things of interest, even if that information is buried deep in our site?

In January 2009, Anderson spoke at the Smithsonian 2.0 conference.2 Organized by the Smithsonian’s new Secretary, G. Wayne Clough, the seminar brought digerati from across the country to discuss how the Institution could make its collections, educational resources, and staff more “accessible, engaging and useful” to our visitors with the help of technology. A few weeks later, the American Art Museum’s director, Elizabeth Broun, continued the discussion by holding an unprecedented all-day staff retreat to discuss the use of social media within the museum.

• • •

Museums are changing. Like many other organizations, our hierarchical structure has historically disseminated information from our experts to our visitors. The envisioned twenty-first-century model, however, is more level. Instead of a one-way presentation, our online visitors are often interested in conversing with our curators and content providers. In response, we in the new media department have been looking for ways to engage our public by designing applications that encourage dialogue. By supporting user-generated content and distributing our assets beyond our website and out across the Internet, we hope to make our content easier to find. In doing so, we are trying to fulfill our long tail strategy. To succeed, we will need to look at our jobs in new ways.

While the traditional visionary makes connections between the big pictures, long tail visionaries look for relationships between the small pictures. I am hedging my bets at the grassroots level. And at this level, I, along with my coworkers, play several roles.

Explorer. Our jobs are to look for and make new connections between our museum, its art, and other online networks. It’s written in my performance plan! Of course, we’ve got a Twitter feed, a YouTube channel for our videos, Facebook pages, and Flickr accounts (we even have a set of images for exhibitions like our recent 1934: A New Deal for Artists3). But we’re also looking for new iPhone apps and other online venues for our work all the time. And with this new interest in social media, there is a lot of potential for connecting with the larger world.

Advocate. Making our artworks accessible and connecting them with Americans’ lives has been our director’s long-term goal, and we’ve noted the cultural shift from a broadcast model of communication (that one-way, top-down dissemination of information) to a more conversational one. Five years ago, when I first proposed doing Eye Level4, American Art’s blog, I looked at how young people were consuming culture. A blog seemed like a good first step toward attracting youth to our offerings and hopefully engendering lifelong interest in our museum. As we develop new social media applications, our job is to assess their usefulness and advocate for their implementation.

When the Lunder Conservation Center5, American Art’s open conservation lab, told us they wanted to find a way to let visitors know when a conservator was working on an artwork, we suggested a social media approach. We showed them how to use Twitter to inform our museum’s information desks that something interesting was going on way up on the third floor. Showing our staff a valuable solution to one of their real-world problems is one of the best ways to advocate for social media within the museum.

Collaborator. It took a group of us to make our blog a success. While our goal was similar, we all saw the process in slightly different ways. Nevertheless, together we made change possible. Growing pains are emerging, though. As we develop new ways of communicating with our visitors and members, our jobs and responsibilities will morph. Bringing order doesn’t require the centralized management of a “Social Media Czar.” But it does require a strategic plan. Who’s responsible for what? How will multiple departments contribute, say, to a Twitter feed without it degenerating into confusion? Organizations used to one honed public voice may find this difficult to fathom. As we try to reach many different audiences, we will want to convey a consistent message. And this can work only if we know how to work together.

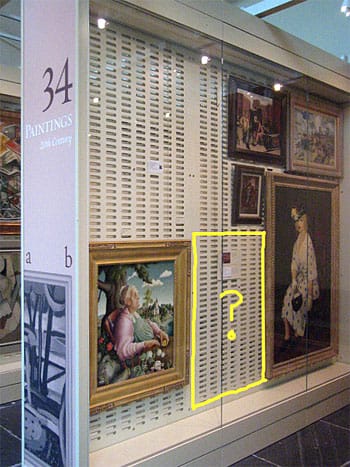

The Luce Center’s Fill the Gap! has been one of the most interesting online interactions we’ve had with our public.

Community Organizer. At the root of all of this techno stuff is people: individuals who share a common interest. We’re finding new ways to bring people together and nurture their relationships with the museum. We do this both within American Art and between our museum and the public. We’re always looking for museum staff to write for Eye Level. Their stories are the museum. As we develop social media outreach, we’re also soliciting outside people to contribute their photographs, insights, and stories.

Recently, the Luce Foundation Center for American Art6, our open storage facility, requested help to Fill the Gap! in one of its cases. If an artwork in open storage is moved elsewhere and will be gone more than a year, the Luce staff replaces the piece with another. This time we asked our Flickr audience for suggestions to fill the empty space. The ensuing dialogue with citizen curators’ suggestions was precisely the type of engagement we want to encourage with our public.7

Realist. It’s not easy developing a new organizational paradigm. I also realize not everyone sees the future in the same way. After our museum’s social media retreat, I discussed the day’s topics with my colleagues. Some had valid concerns and reservations. How would this new goal add to their already busy jobs? With resources at a premium, would the quality they strive for be sacrificed? And with so much “junk” on the Internet, would our efforts just be adding to the cacophony? Good content is still our best cultural currency, and we have a lot of it here. Plus, as I see it, face-to-face dialogues would always trump anything online. It isn’t the technology I am excited about, but rather how technology can connect us and even lead to new understandings about our content.

As long tail visionaries, we don’t just embrace new technology, we question it. After the unbridled exuberance for the 1990s’ next best thing, separating reality from hyperbole has become one of our most valued skill sets. Our efforts must support our museum’s goals, but we can test these waters, even failing now and then, and still move forward and evolve. Developing new paradigms require more process-oriented rather than results-oriented thinking. We have to be aware of the new structures and relationships we’re building to evaluate our successes and failures. This is the grassroots where long tail visionaries work best.

• • •

Is it hubris to call us visionaries? Not really. We are part soothsayer and part prognosticator. And these have become entry-level requirements for cultural workers at any organization. At the very least, we need to make informed decisions and a lot of educated guesses about the changes technology is bringing to museums. Is it provocative? Change, by its very nature, is provocative. Traditional museum content providers are no longer the only people in a position to decide what is worthy of our attention and limited resources. Museums and other cultural institutions are in the midst of a fundamental shift, and long tail visionaries are working together with curators, public affairs officers, and other staff to make some critical decisions. This transition, though, will not always be easy.

Sometimes I need to be a realistic and pragmatic long tail visionary. But, I’ll confess, now and then, I can also get really, really excited by the possibilities. Visionaries can get that way sometimes.

Endnotes

1. Chris Anderson, The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More, Hyperion, 2006

2. Smithsonian 2.0 Initiative, Pew Research Center (Updated October 2021)

3. Smithsonian American Art Museum exhibition: 1934: A New Deal for Artists, http://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/archive/2009/1934/

4. Eye Level, http://eyelevel.si.edu

5. Lunder Conservation Center, http://americanart.si.edu/lunder

6. Luce Foundation Center for American Art, http://americanart.si.edu/luce

7. Fill the Gap!, http://www.flickr.com/photos/americanartmuseum/sets/72157613328866883/

© 2009-2021 Jeff Gates. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License.