19 Nov It Seems Like More Than a Century

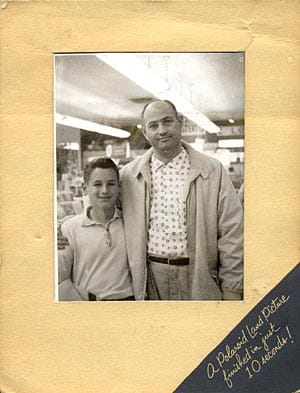

My father and me, taken in the early 1960s, when we encountered a demonstration of the brand new Polaroid instant camera. Funny how I eventually became a photographer.

Today marks the centennial of my father’s birth, November 19, 1921. He died in 2000. We had a complicated relationship, and I’ve spent a good deal of my life investigating his life to better understand why. He never talked about his childhood. So I had to dig for that information. In the end, I did my best to be a good son and to honor him at the end of his life.

I got a call from my father’s second wife, Vera, at the office at 11:30 am that October. She was crying, which was very unusual for her. I’d never seen her cry. She was distant. My father was in the hospital, and I’d better get out there. I called my wife, asking her to pack for me. I called the airline, and by 6 pm, L.A. time, I was on the 405 on the way to his hospital bed.

I stayed there for ten days. But then, I had to get back to work. Yet we knew the end was near. I changed my flight to the afternoon to come back for one more visit the morning I left. He was asleep, and I don’t even know if he knew I was there. But I wanted to make this passage different than it had been with my mother’s death. I sat there and looked at every inch of him, from his head to his toes. I wanted to remember him as best as I could. Then I left. I never shed a tear.

Two weeks later, he died. And, once again, I flew from my home in D.C. to L.A. for his funeral. I arrived at the mortuary early. They asked me if I wanted to take a final look at him. I started to walk into the room and forced myself to stop. I turned around. I wanted to remember him alive, not dead. It took a lot of energy to turn around. Inertia is real.

His funeral was actually like an Abbott and Costello movie. The rabbi had been an old family friend of my mother’s (who had died many years before), and, during the ceremony, mixed up my mother with my Vera (she was horrified; I laughed to myself). When he said my father graduated from UCLA, I had to speak up: “No, he graduated from USC. I graduated from UCLA.” I got the last word, Dad!

That October, I spent 20 hours in the air, and I used all of my time writing about my father on my Palm Pilot. I kept those remembrances but vowed I would not take a deep dive into writing about him until Vera was no longer here. I certainly didn’t owe her anything, nor did she owe me. But I didn’t want to hurt her nonetheless. She died last year, and I know exactly where all those notes are. But I did write small snippets about our relationship. Here’s part of one missive I wrote about him when Ronald Reagan died called “A Final Gift For My Father.”

“In my father’s final days, I asked him if there was anything I could do for her after he died. I had tried to think of everything I wanted to say to him, and, as difficult as it was for me, I added this to my list. ‘Love her,’ was his strong and clear reply. ‘Love her.’

“If ever there was a person who made it clear she didn’t want anything from me, let alone my love, it was Vera. But I told Dad I would do my best, not knowing how I could ever hope to fulfill his dying request.

“When I told a good friend my dilemma, she replied, ‘But Jeff, you already have loved her. When you told her you would be there for her, despite your differences, you did so without any thoughts of getting something in return.’ So I had. I was relieved and surprised. How did I learn to act so maturely, to face the difficult issues head-on? This was a new kind of love: a very difficult kind.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.