And the Process-Oriented Shall Inherit the Earth

Are you process-oriented or are you results-oriented?

Creating new museum projects is becoming more complex. The development of exhibitions, websites, and social media outreach requires multiple departments to work more collaboratively than ever. Content creators must communicate effectively with web producers and editors. A change of text can require a shift in context: site architectures may shift, and everyone must be aware of how these changes affect the development process and project timeline. But who’s watching over this complex process? And why is this even important? As technology and our workflow change, paying close attention to our approach becomes more critical. So let’s start with Glenda’s question: Are you a good witch, or are you a bad witch? I mean, are you results-oriented, or are you process-oriented?

Museums, like most organizations, are results-oriented. Directors want projects to come in on time and budget. While we all want our projects to succeed, benchmarks for success and engagement are constantly changing. This makes gauging our results more complex and, often, getting there even more so. These new paradigms frequently require new ways of planning. What worked last year may not work or be valuable this year. To paraphrase the old real estate adage: the three most important words in this environment are context, context, and context. The process we use to reach our goal is becoming as important as the results.

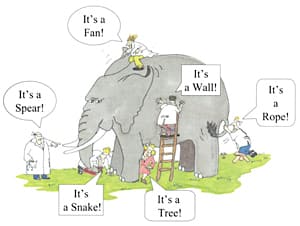

Often, project management seems like the parable of the twelve blind men. Each person on the team is looking at the undertaking in their own way, based on their own part in the project. Stakeholders have a vision of what they want and give technologists a list of deliverables. Technologists take that laundry list and put it together to find the right tools for the project. But technology and the mission of our museums are fueling changes in how we approach this process. And this affects how we, as technologists, approach our jobs.

Often, project management seems like the parable of the twelve blind men. Each person on the team is looking at the undertaking in their own way, based on their own part in the project. Stakeholders have a vision of what they want and give technologists a list of deliverables. Technologists take that laundry list and put it together to find the right tools for the project. But technology and the mission of our museums are fueling changes in how we approach this process. And this affects how we, as technologists, approach our jobs.

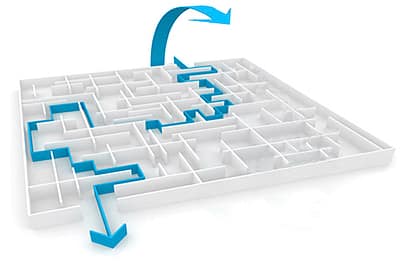

Results-Oriented: How quickly and efficiently can we complete the project. Process-Oriented: Visualizing project development from beginning to end.

Put simply, results-oriented managers have a goal: How quickly and efficiently can we finish the project? This is traditional project management, where the primary emphasis is to get the project done on time, on budget, and within scope. In contrast, process-oriented people look at things a little differently. For them, success rests with visualizing project development from beginning to end to finish on target and on time. This is what I call meta-project management. The primary emphasis is how are we going to obtain our goals? Both approaches are necessary for success. Without a plan, there is no project. But once you have one, you need to know how you’re getting there.

Is this what I’m talking about?

No, not quite.

Managers and stakeholders are interested in a broad project scope: are we on target? They have no time to drill down to the details. Workers tasked with developing technology projects deal with the details. They need to know what’s happening at all times to monitor benchmarks, troubleshoot, and, ultimately, bring the project to fruition. Process- and results-oriented project management styles are not necessarily mutually exclusive. We often play both roles throughout the project lifecycle. And technologists must be aware of both approaches. We want the project to succeed, and we want our managers and stakeholders to feel confident about the process.

As new technologies encourage new types of projects, the roles of museum staff are changing. And, if we’re not careful, we will slip into that twelve blind men and the elephant paradigm. Here’s a personal example: When I was asked by my supervisor, “How’s the project going?” she wanted to know if it was on target? But rather than give her a direct answer, I started telling her the issues I was dealing with at that particular moment. I was focused on the process. She was focused on the product. I took note of this disconnect and decided to take a different approach the next time. A few weeks later, when she asked me for an update, I answered with the information she wanted (“The project is on schedule.”). Once she had what she needed, she was more open to hearing about the more specific issues I was facing. It was a win-win.

Technology is accelerating organizational change. And this affects our development process. By focusing on this process, we can become more agile in our project development. And we can better anticipate potential problems and roadblocks. But for technologists, this can be a Sisyphusian task. In 2010, I presented a paper at the Museums and the Web conference called Clearing the Path for Sisyphus: How Social Media is Changing Our Jobs and Our Working Relationships. In it, I mentioned seven roles technologists were now playing in the social media-focused workplace. We are:

Advocates: advocating for change

Collaborators: working with others for change

Community Organizers: working to build communities both with our visitors and within our organizations.

Realists: Accepting the often slow pace of change and resistance to new ideas.

System Analysts: Looking at the process of introducing and developing new ideas.

Negotiators: Negotiating for change. Building alliances within our organizations.

And finally, we are Opportunists, looking for new ways to approach the process whenever we see an opening. We can also apply these roles to project management.

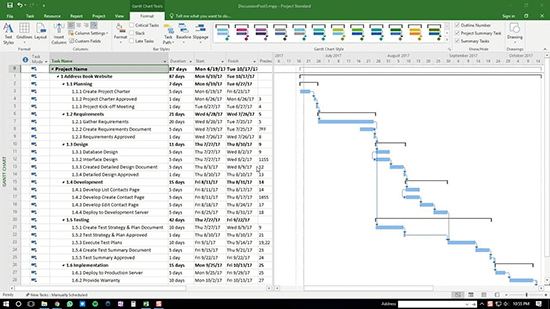

A Traditional Microsoft Project Schedule

Dorothy had the Yellow Brick Road as her roadmap. We have Microsoft Project, an application only a traditional project manager can love. As a technologist, it’s confusing and easy to get lost. Of course, someone needs to be looking ahead. But these days, it’s not just the project manager. It also is the project technologist.

In a talk Nina Simon gave at the Smithsonian in 2009, she stated science museums engage their audiences much more than art and history museums. She wasn’t sure why. Science curators, I tweeted in response, are scientists whose experience is rooted in collaborative inquiry. Engagement is an essential part of their process. However, art and history curators come from disciplines where personal research is the keystone of their research. When new curators begin working at an art museum, they are less likely to have worked in a collaborative technology environment. Does this make a difference in how we develop projects that encourage visitor participation? If so, how can we foster a more collaborative and process-oriented development environment? The key is to remember the roles technologists play and take the opportunity to use them throughout the project lifecycle.

A Case Study: Oh Freedom!

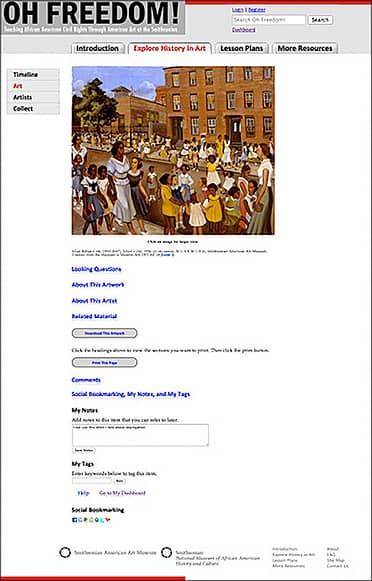

An Artwork Page from the website “Oh Freedom!”

In 2011, the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Museum of African American History and Culture completed an online project called Oh Freedom! We developed the site to help middle and high school teachers use American art to teach African American civil rights.

In our initial meetings, the stakeholders shared the content they wanted to see on the site. The number of necessary elements on each artwork page included a large image and information about the work and the artist, related material, and questions to help students look at the art. As I listened, I mentally prioritized each piece of information. Most importantly, they wanted teachers to be able to collect and annotate information on the site for future use using a “My Collection” widget.

The challenge was to get them this feature with a content management system (CMS) that would also work for the other elements of the site. I began looking at CMS’s that offered this “My Collection feature because this would be the most difficult to fulfill.

One of the only CMSs I found was Omeka, an open-source system developed at George Mason University in Virginia. Omeka was explicitly designed for museum collection and exhibition websites.

Since the stakeholders wanted an abundance of information on each artwork page, to make it easy to navigate, I used an accordion script to hide and reveal the details of each section. In addition to the “My Collection” feature, another important element on each artwork page was “Related Material.” Secondary sources allowed for a broader look at civil rights and American art.

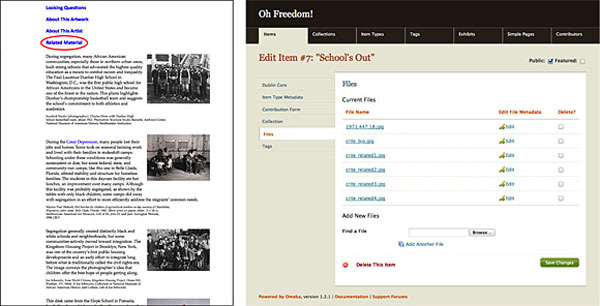

Left: an expanded view of the related material. Right: Omeka backend for managing this information. In an early version of the CMS there was no way to reorder the list.

During my initial testing, I noticed a significant limitation in Omeka’s ability to handle and display this related information. Once you input the data and images on the backend, you couldn’t reorder them! Therefore, I would need to upload all data in the order it was to appear on the final site. In subsequent versions of the CMS, ordering was allowed. However, the plugin for the collection feature wouldn’t work with these newer versions. So, given the priority of the collection feature, I was forced to stay with this earlier version of Omeka.

I needed to convey this challenge to my stakeholders immediately as it had both immediate and long-term ramifications for the project’s development. Constant updates to a site before launch are common in web development. I foresaw major time constraint issues if I didn’t get all the information in the correct order the first time around. And I needed to communicate this to the stakeholders. We needed to create a detailed chart showing the exact order of each group of related material for every artwork. And final decisions had to be made early in the implementation. This would not be a typical project.

Technologists have to be aware of multiple processes throughout the project. I had to manage development, but I also had to communicate to my stakeholders the limitations of the content management system and how that would affect their work and the overall project management timetable. When the stakeholders complained about the software’s limitations, I reminded them that we were using it because their priority was the “My Collection” ability. The only other way to do this was to create a CMS from scratch. And we didn’t have the budget or the time for that. So, as part of this process, technologists need to be ready to justify their choices when issues like this arise.

This process-oriented approach to project development mirrors the changing relationship between our museum and our visitors. Rather than focus on just the results of art-making (the art), we also focus on the outreach process through social media, behind-the-scenes activities, and conversations with our patrons. We can apply the strategies we’ve developed to engage our audiences in how we approach project management. The key is to remember the new roles we technologists play and take the opportunity to use them throughout the project lifecycle. And slowly, we are pushing that Sisyphusian boulder up that hill.

So let me return to where I started and leave you with this question: when are you process-oriented, and when are you results-oriented?

Originally titled And the Process-Oriented Will Inherit the Earth, I presented this talk at the 2012 Museum Computer Network Conference in Seattle, Washington.

© 2012-2021 Jeff Gates. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License.