New Roles for Artists in the Information Age

This article was originally published in 1996, commissioned by the New York Foundation for the Arts’ publication FYI. It was also the basis of my keynote address to the National Council of Arts Administrators Annual Conference that same year. Given it was written at the dawn of the internet, it still is a cogent blueprint for artists in the 21st century.

• • •

The futurist Alvin Toffler writes extensively about powerful culture and social shifts now taking place in our world and how to cope with these changes. Astute politicians and cultural critics study him as we all struggle with yet another “New World Order.”

Understanding the nature of information and its dissemination offers us important clues to our future. Adjustments will have to be made in the way artists work if we are to survive and prosper. And if artists are the antennae of the society, as Ezra Pound once said, then society at large can also learn from us, noting how we process and use new technological tools.

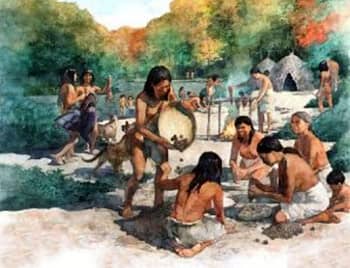

Hunters and gatherers hunted and grew only what their tribe needed.

In his book The Third Wave, Toffler discusses three major social shifts in human history: the agricultural, industrial, and information revolutions. In the agricultural age, which lasted tens of thousands of years, isolated, self-sufficient communities not only grew all their own food, but also produced everything necessary for their lives. Artists, as object-makers and ritual leaders, played a central role in village life, with a direct impact on both the economic and belief systems of their communities.

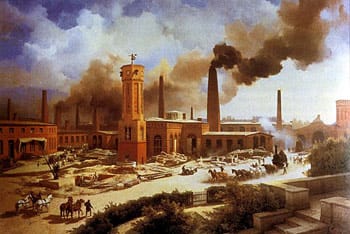

In the 19th century, the Industrial Age marked the invention of labor- and time-saving devices. With the help of these machines, more goods could be produced than any one isolated community needed. And new markets developed for the excess. The development of steam power, the railroads, and the internal combustion engine allowed this surplus to be transported to these growing markets.

New inventions led to more goods and larger markets.

Artists, too, became producers of goods to be bought and sold in a new art marketplace. Artists’ social importance to their communities became secondary to the objects they created for sale. As their products were bought and sold by middlemen such as galleries and dealers, their place and importance in society moved from the center toward its periphery, in guises ranging from craftsman to malcontent. This was the dawn of artist stereotypes as they have been passed down to us today.

• • •

Today, the art market, like other markets, is based on a stratified system of producers and buyers. Gallery dealers serve as conduits between artists and collectors. But resources are limited, so commercial galleries cannot support every good artist.

Since the structure of the net is more open, we have much more access to information and a much greater opportunity to provide that content directly to the consumer. As Napster suggests, it is easier (albeit not “easy”) to compete with large corporations like Sony and Disney than it was 25 years ago. Yet our ability to do so is not guaranteed.

Corporations are attempting to define the internet in their own terms to protect their products and expand their market share. First the music industry and now the film studios are fighting to control access to content. Digital media are easily copied. The Supreme Court is presently hearing arguments on the viability of our copyright laws: who owns the content and for how long. In addition, the tools to create one’s own high quality digital film are now within the reach of many.

With the net offering new ways to create, produce, and distribute independent content CEOs and CFOs are becoming nervous. Artists’ freedom to create and market their work could change if we do not become knowledgeable and invested in the process now.

At a recent “town meeting” of the Washington, D.C. arts community, a gallery owner gave us some statistics. In the two and a half years he has been in business he has had 17 exhibition slots. Seven shows were reviewed by the news media, but only two got more than a one-paragraph mention. The odds of finding a gallery who will take on our work and exhibit it are small. Getting media attention, which could fuel sales, is even smaller. Is there another way?

Why not take some control over how and to whom our content is circulated? Information placed on the net has a potential readership of 500 million people (when I first wrote this article in 1996, the number was 37 million). By 2004 this number is projected to be over 700 million. I founded Artists For a Better Image (ArtFBI), a non-profit organization that studies stereotypes of artists in the media. When we opened our website in 1994, it attracted more than 10,000 visitors in the first three months of operation. For a small organization or an individual, that’s a lot of coverage. The traditional art market has its purpose. But it is no longer the only avenue we can take.

Artists will be needed as content providers in this new Information Age.

As the information-based society develops, the market will require more and more of this information commodity. Artists are extremely well placed to deliver important cultural services by providing and interpreting this content. With the web capable of handling sound, short animations, and video, composers, media artists, writers, and visual artists will find online vehicles for their work. In addition, as corporations scramble to get their feet in the cyberdoor, they will need good content creators.

How we get our information is changing. If artists want to change with it, they must find two good vantage points within the shifting techno-maze: one relates to process and the other to content.

• • •

At a time when we are overwhelmed with new information, most people have difficulty finding what they need. How do we sort through the huge amount of material being created? Artists are masters of the search, often drawing on intuitive hunches to make hidden or obscure connections. The following personal story will illustrate what I am talking about.

One day when I was in my mid-20s I bought a pot roast. I had no idea how to cook it and no cookbook to consult. Given my situation, what was the quickest way to find out? I thought a minute and then picked up the phone and called 411: “This might sound like an odd request,” I said to the Operator, “but could you tell me how to cook a pot roast?” She laughed and proceeded to give me her recipe. Within minutes I was preparing my meal.

My unorthodox methodology at the time (there was no internet back then) yielded quick results and germane advice. I used the latest technology to find what I needed. Knowing how to take the first step is the key and artists are good at that.

Until recently, much data could only be found and interpreted via “gatekeepers.” Doctors, lawyers, and politicians, for example, controlled information through the use of specialized terminology often found in professional publications. Our access was limited and often required explanation by experts. Yet this hierarchical system is beginning to break down.

What we know and how to find and interpret information are becoming important factors in an individual’s ability to succeed and understand complex and often changing ideas. Artists already possess the expertise necessary to find different ways to navigate and develop new and non-traditional methodologies for knowledge organization and interpretation. Given the reorganization of cultural systems, this presents an important opportunity for artists.

• • •

One of the major differences between today and previous eras is the acceleration of change. The agricultural age lasted thousands of years and the industrial age 150 years. The new communications structure is constantly redefining itself. Everyone feels overwhelmed and overloaded by the pace of change and predicting the future. The shift in process is causing major upheavals as everyone, even top executives, struggle to stay ahead of the curve.

The information revolution is more than just the internet and its residual hyperbole. It is a cultural shift from the political and social systems that controlled the flow and content of information to one that offers individuals more direct involvement in the developing social structure. Artists need to be involved in this process.

The nature of the medium offers the potential for us to reach large or very specific audiences as content providers and interpreters. The pace and scope of these changes often seem daunting, especially if we have no prior experience with the tools. But the chance for artists to reposition ourselves from the stereotypical fringe to a more central and valued position is too good to pass up.

© 1996-2025 Jeff Gates. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License.