24 Apr On Talking to Strangers

Never say a commonplace thing.

Jack Kerouac

My name is Jeff Gates and I talk to strangers. More on that later.

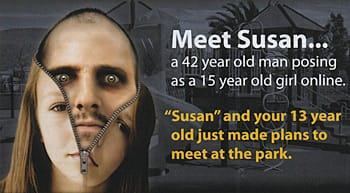

We don’t want our children to be fearful of public engagements. But we want them to be able to understand the risks. Illustration from an ad for online security software.

With one bona fide teenager and a proto soon-to-be teen in the house privacy has been a hot family topic. Well, only their parents seem to think it’s an important issue. The girls seem totally nonplussed. And that’s our point of contention. My wife and I are trying to teach our children about the boundary between public and private space in a world that seems to be working against us. The boundaries are constantly changing and we can’t rely on our upbringings to guide us. There was no Internet when we were kids. Children have unparalleled access to information. But they have no real world experience with what to do with it or how to engage it.

Thursday, Nina Simon, who has written a great deal on the participatory museum (and has just published a book about it) came to the American Art Museum for a talk. Museums are morphing. The old hierarchical authoritative paradigm–we are the experts and we invite you to come to us for knowledge–is changing. In this Web 2.0 world museums are now beginning to engage our visitors in dialogues, not lectures about our collections. Nina has written a lot about this process and her experience is helpful in understanding this challenge. Her topic in a nutshell: how can we talk with strangers who come to our museums and how can we devise situations where visitors can engage other visitors?

I love talking with strangers, both online and in the real world. But I’ve devised some fuzzy rules for these engagements. So how do I reconcile this with my concern for privacy and the education of my girls? The answer is context.

Interestingly, Thursday was a banner engagement day for me. I had two of the most intriguing conversations with strangers within hours of each other. At lunch I was sitting in the cafe at Barnes and Noble sipping a coffee and surfing the net. Sitting next to me was a man on the phone. Being the voyeur that I am I overheard him talking in his Irish accent to an airline, trying to confirm his flight home the next day. When he got off I turned to him and asked if the volcano had stranded him. I mentioned that I had just come home from a conference at which many of my European colleagues were struggling with the same issue. But before I approached him I assessed the situation. He didn’t appear to be threatening; we were in a public place; and I could leave if I needed to. The assessment was cursory (I didn’t ask him for references) but I also relied on my past experience to continue. Let it be known I’m not one of these chatty strangers who will talk with anyone about anything. I have boundaries and I respect others’. He asked me what I did.

He works as a researcher for the Dictionary of Irish Biography, part of the Irish Royal Academy. He was at the bookstore for its free WiFi and a conversation about the Net and the changes cultural institutions like ours are encountering ensued. It was an amazing and serendipitous encounter with a total stranger. And if I hadn’t connected with him on a common ground (the volcano) we would have never had that conversation. And wonderfully we are now in contact with each other.

A few hours later I was grabbing a bite to eat at Starbucks before Nina’s lecture. As I sat down at a long table a man was standing next to a woman talking about mathematics. At first I thought he was trying to pick her up (and indeed math might simply have been his entry into her world). She appeared to be a bit uncomfortable with the engagement, explaining that she had done her PhD on the subject and worked for the National Institutes of Health. It appeared her credentials were her only defense but he ignored them. And when he finally left she was pissed. She immediately called a friend. “Why do men think they know it all,” she said. I listened (hey, it was a public space and I was two feet from her). She was disgusted. And I seriously wondered if I should enter her world. I had something to say in defense of my gender, but should I? I decided to but I was prepared to disengage if it was clear I was adding to her discomfort. Yes, I actually thought this through. I would take a chance but, given the context and sensitivity gender plays today, I was prepared to apologize and leave if need be.

She got off the phone, we made eye contact, and I said: “Not all men are like that.” She sighed and explained the whole encounter. When she was finished I replied: “Perhaps the only thing you can do is to raise a son the right way.” She laughed and thanked me for adding a bit of levity to a situation she obviously faced often.

Two radically different encounters with strangers. Yet each was rich, adding a bit more to all of our experiences in those public moments. Whether on the Net or in a coffee shop, the notion of public and private space is changing. And we’re struggling with it just like our institutions are.

So after Nina’s lecture about engagement, I stood up at the Q and A to ask her to talk a bit about a workshop she’d given to a group of teenage girls on how to talk with strangers. Her reflections on teenage interactions were interesting but my parental experience made me feel there was a piece missing. Nina had provided these girls with tools for talking to strangers (signs and ways to pose interesting questions to query strangers) but I was looking for how to teach teenagers to assess the context of an engagement, just like I had with my fellow strangers.

Nina responded to my concern by stating that most dangerous encounters were with people who knew each other. I agreed with her stat but I still felt uneasy. In October 2002 DC’s sniper John Allen Muhammad used our neighborhood as a random shooting gallery. Experiences like this inform our lives. I just don’t want these to run our lives.

A few years ago my intelligent older daughter opened a gmail account (without our knowledge) and was emailing a “girl” who worked at Cirque du Soleil. Yikes. She was so trusting of basic information without any skill to assess its veracity. This is a learned thing. But how should we be teaching it?

I don’t have a pat answer. But, for the moment, I believe it’s something that will come in time as my wife and I reinforce what I call “healthy paranoia” to our children. Privacy and public engagement are not mutually exclusive. Ten years ago when I started posting online missives about my family I set some rules of the road for posting personal information. These are malleable, changing with each context. We don’t want our girls to be fearful of every public nook and cranny. But we do want them to understand that looking at the context of these engagements is important for their safety and success of these encounters. It’s a calculated risk.

But risk taking is not a science, although I wish it was.

- [ Nina Simon, Web 2.0, Internet Safety ]

Howard

Posted at 15:24h, 24 AprilI had experience with both kinds of danger — a well-known member of the community who turned out to be a child molester, and a well-publicized instance of a dangerous stranger. Statistically, out of one million children online, 6 are going to be molested by someone they meet online and 50,000 are going to be abused by a family member, babysitter, or neighbor. “Stranger danger” on the Internet is a moral panic.

In regard to the public sphere, I told my terrified 8 year old (she later took karate lessons, which dealt admirably with the terror) to be a good citizen. If a stranger asks for directions, give him directions — but stand out grabbing distance. And if he tries to grab you, put your pencil through his throat.

Jeff

Posted at 09:12h, 26 AprilAs an interesting addendum to this subject, this morning on NPR’s Morning Edition they had an interesting story on Williams syndrome, a genetic disorder. People who have this disorder are totally trusting. The story profiles a mother as she tries to teach her daughter to distrust.

Susan

Posted at 13:16h, 30 AprilIt seems to me that safety while talking to strangers is about having social skills and learning to read social cues, right? You probably relied on a number of cues when assessing the openness of your strangers in Starbucks and B&N–body language, eye contact, language, volcano status…

“Social” skills in the online world are a little different than those in the real world. We’re all trying to figure out how to find and read those online cues. I wonder about kids growing up today, spending so much time online — Do they see a difference between online and in-person social cues? I think you are right that these things need to be taught. I think the schools are grappling with this as we speak. But because so many teachers are not as savvy online as their students, it presents a problem and is challenging traditional ways of education and learning–which I think is the point of much of Nina’s work.