Barrio Mobile Art Studio

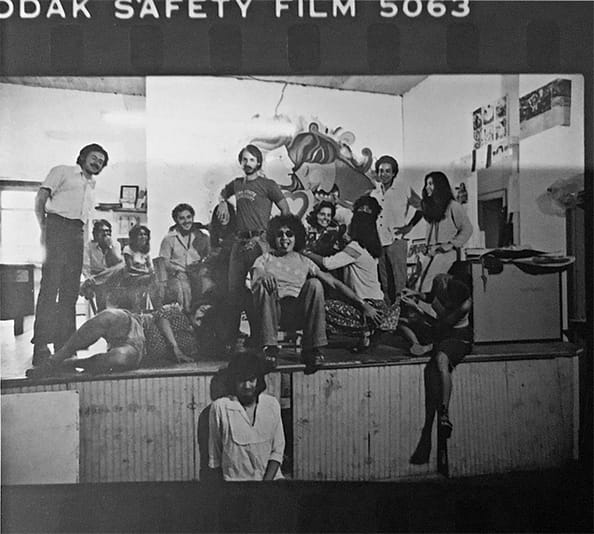

I’m the bearded guy in the middle standing with my arm on my hip.

I completed grad school in 1975. And it was time to start living my life as an artist. I wasn’t sure exactly what that entailed. But I knew I needed to find work, preferably a job that involved art. When I found out that Self Help Graphics in East Los Angeles was looking for artists to teach in their community, I was intrigued. Founded in 1970 by Sister Karen Boccalero and Mexican artists Carlos Bueno and Antonio Ibáñez, Self Help was one of the first community arts centers in Boyle Heights, a predominately Chicano part of the city. And they were launching a new program, the Barrio Mobile Art Studio. They had bought an old UPS delivery truck and outfitted the inside as a darkroom. Sister Karen hired eight artists-in-residence, and she divided us into two teams. Each included a photographer, a painter, a sculptor, and a puppeteer. We would be going out to schools and community centers teaching both children and adults.

While I grew up in Pacoima, part of the San Fernando Valley, I knew the history of Boyle Heights, part of East LA. My mother grew up there. At the beginning of the 20th century, the community was one of the few in Los Angeles where people of color were allowed to live. And by the 1920s, Boyle Heights was a mix of Jews, Mexican-Americans, and Japanese-Americans. Looking at my mother’s 1939 senior yearbook from Roosevelt High, it’s clear she lived in a diverse community. Today, the area is about 95% Chicano.

Pacoima in the 1950s and 1960s was very much like Boyle Heights had been. It was a mix of White, Chicano, Blacks, and Asians. It, too, had been redlined. Pacoima was the only part of the Valley where Blacks could buy homes. I attended San Fernando High School, a decade or so after Ritchie Valens. The school was “multicultural” decades before the term became part of our lexicon. Over the years, my former classmates and I have talked about our lives back then. Given today’s politics and social realities, we agreed that race didn’t segregate us as much as socio-economic class. As Pollyanna as it may sound today, the color of our skin was never much of an issue in the college-bound groups we were part of. Not that it was a colorblind Shangri-la. Chicanos and Surfers often butted heads, or worse.

Between my mother’s connection to Boyle Heights and my experience growing up, I felt comfortable with the sounds of Spanish spoken on the streets and the smells of pan dulce coming from the bakeries in this Chicano community. The fact that I was the only Anglo hired was never an issue as it might be today. I loved the culture, and both Self-Help and the community welcomed me without hesitation.

My time there was instrumental in my development as both a teacher and an artist. Throughout grad school, the subject of my work centered on an inward look at myself. But this changed at BMAS. My trajectory as an artist shifted to community, social, cultural, and political subject matter. And, after four decades, it hasn’t changed.

A Project of Interest

Two self-portrait dolls I did of myself.

One of the more exciting teaching projects I helped develop was teaching children to make self-portrait puppets and dolls. It was a terrific way for our students to express their identities. I worked in collaboration with Carla Webber, the puppeteer on our team.

In our first session, I’d take each student’s portrait. I’d go back to the darkroom at Self Help and create large negatives of their faces. At the next session, usually a week later, I’d show them how to make cyanotypes (blueprints) of their faces by coating canvas with a light-sensitive solution. They’d place the negative on top of the coated canvas, put it in the sun, and watch it “develop.” The kids were very excited to see their images printed on the canvas. These would become the heads of their puppets. Carla would then show them how to make their bodies, first using aluminum foil to mold the body and then covering it with paper mâché. The final step was to make the clothes. We had piles of fabric pieces, and Carla helped the children sew their clothes. After I left the program, I gave workshops for elementary school teachers on how to do this with their students.

Piecing the History Back Together

It’s been almost fifty years since the Barrio Mobile Art Studio program began, and art historians are now studying and writing about it. I hadn’t been in contact with anyone in the program for decades. Recently, I spoke with Theresa Avila, Assistant Professor of Art History, at California State University Channel Islands. She is researching the history of the BMAS. History, as I’ve learned, is not set in stone. Some of it is documented, but each of us is coming back to it from a different vantage point. Putting these perspectives together, weighing memories, and writing an accurate account is an arduous task.

But Avila is not the only one trying to piece this together. In 2018, now living in Washington, D.C. and working at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, I first connected with this part of my past. As luck would have it, J.V. Decemvirale, a pre-doctoral fellow at the museum, was doing his dissertation on the activism of Chicano and Black arts organizations in LA from the 1960s to the 1980s. And he’d been looking for me. Well, not just me, but everyone who worked at BMAS during that period. From that conversation, I interviewed him about his work for our museum’s blog.

When museum fellows gave talks on their research in the spring, I made sure to attend J.V.’s. My memories were percolating and resurfacing. As I sat there listening to his words and looking at his PowerPoint, suddenly I saw myself as a 25-year-old in a photo of the entire group of BMAS artists (which you see above). Afterward, I said to him, “Did you know I was in one of the photos you showed?” He didn’t. Another little piece of history resurfaced.